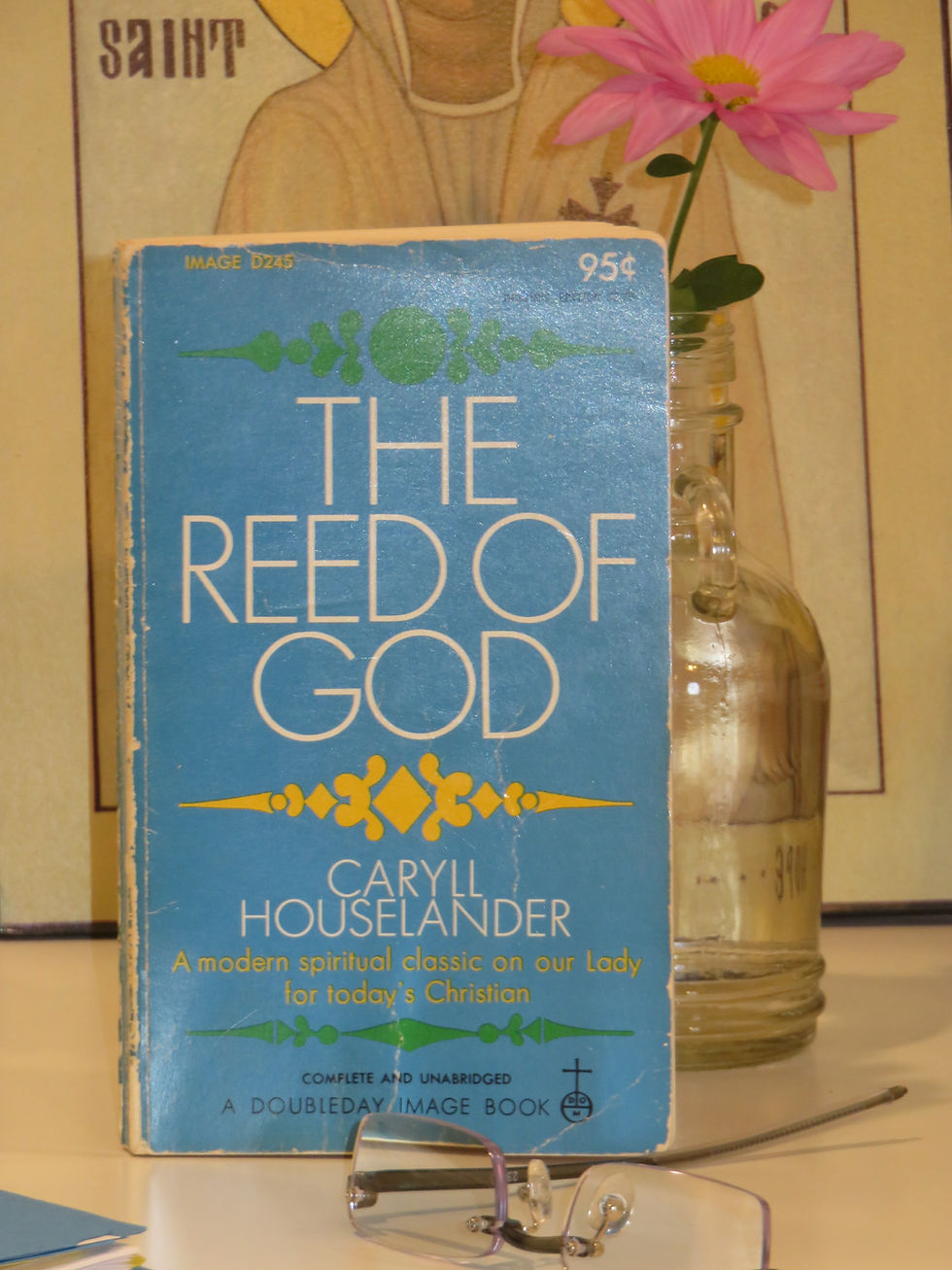

The Reed of God

- CFR Sisters

- Nov 27, 2020

- 4 min read

Friday Book Pick:

The Reed of God by Caryll Houselander

Ordinary time, hand in hand with Thanksgiving, slips quietly out of the dimmed and contented house, holding open the door for Advent, who makes a graceful entrance as Holy Mother Church sings in the new liturgical year with her evensong.

Advent is a wondrous season of expectant joy mixed with a touch of melancholy. Barren trees and barren earth remind us of the emptiness of a waiting world. The sun’s late rising and going earlier to rest makes us yearn for the light. All of creation seems to conspire to draw our attention to the horizon—ready to be awakened with new dawn. And so, we settle into a quiet watchfulness and wait again for the fullness of time. Reliving the mystery is the magic of the liturgical year, and our living Catholic memory makes new grace possible out of ancient history.

Today’s book pick is an Advent read. Advent is Our Lady’s season. If Caryll Houselander was aiming to write a Marian classic, a work of insight and depth whose value spans generations and continents, she has accomplished the task with The Reed of God. First published in England in 1944, it is still in print—still being read.

This small book is best consumed one little morsel at a time. If reading is to be a spiritual exercise, and not only a relaxing pastime, a slow and ponderous approach is helpful, a slow reading of a few lines until something captures your attention. Then pausing, lower the book and close your eyes and—almost unnoticed—the seeds of your pondering will bloom easily into prayer. The Reed of God was written for this kind of reading.

The Blessed Mother that is introduced in the pages of this book-length meditation is not the two-dimensional Madonna of the laminated “holy card” or the regal Blessed Mother of the gold-gilded Christmas card. The Mary of Nazareth that Caryll Houselander tries to get across to her readers is the flesh and blood woman who lived 2000 years ago and who lives even now, crowned as Queen in heaven.

Houselander asserts that Our Lady is misunderstood (by some) precisely because of her virginity. “There are two things that make it difficult for many people to love Our Lady…that she is pure and virgin. There is nothing so little appreciated today as purity, nothing so misunderstood as virginity.” The reason Caryll Houselander sites, writing in 1944, is poor example, comparing some virgins to sour apples. In 2020, I don’t think the misunderstanding about virginity is due so much to poor example as to no example. Today people look on virgins as they would look on martians—with skeptical disbelief. Yet Houselander, a poet and a mystic, seems to possess a deep understanding of the theology behind chastity, and she manages to convey the beauty of Our Lady’s unique virtues and the glory of her perfection. She explains virginity as: “really the whole offering of soul and body to be consumed in the fire of love and changed into the flame of its glory. The virginity of Our Lady is the wholeness of Love through which our own humanity has become the bride of the Spirit of Life.”

Another problem in adequately appreciating Our Lady is the lack of knowledge we have about her—so few words, so few details. It is often precisely the human details—even the foibles—that attract us to the saints, because these details can help “bridge the immense gap between the heroic virtue of the saints and our weakness.” We are drawn to the humanness of the saints. Have you seen the image of Blessed Pier Giorgio clenching a pipe between his teeth as he ascends a mountain face? I don’t think I am the only one who just likes the idea of a saintly pipe smoker. Maybe you, like me, are consoled by the thought that St. Thérèse experienced annoyance at the habitual noise made by one of her sisters in the otherwise silent chapel. It is touching to know that Blessed Solanus Casey loved to play the fiddle even though his brothers attest that he wasn’t very good at it. These little glimmers into the humanity of our heroes make us feel that they really may have had something in common with us. It is precisely these personal details that we do not know about Our Lady: what she liked and what she didn’t, whether or not she played an instrument, what she grew in her garden. “Of our Lady such things are not recorded. We complain that so little is recorded of her personality, so few of her words, so few deeds, that we can form no picture of her, and that there is nothing we can lay hold of to imitate. But it is Our Lady—and no other saint—whom we can imitate.”

Houselander makes an interesting contrast between our Blessed Mother and the other saints, each of whom, because of their particular vocation or human characteristics, have their special niche in the Church, but Our Lady, she says, is “not only human; she is humanity.” What Our Lady did and does “is the one thing we all have to do, namely, to bear Christ to the world.” This thought—this mission—to be Christ-bearers in the world is the golden thread woven throughout this marvelous Advent meditation The Reed of God, and through all of Houselander’s works.

With metaphors such as the reed, the nest and the chalice, Caryll crafts a poetic lesson on the meaning of virginal emptiness.

Our Lady’s fiat becomes the standard as Houselander gives a teaching on what †Fr. Benedict called the secret of the spiritual life: trust.

In her chapter on Advent we walk in the silence of Our Lady as she awaited the coming of the Light of the World. The Light she carried in the darkness and the silence of her womb.

Yes, this is much more than a book. The Reed of God is a profound meditation on Our Lady and on Jesus Christ her Son. If you decide to take it up for spiritual reading this Advent, it will carry you to Christ’s holy birth—and far beyond.

Mother Clare, CFR